by Gerard Haggerty

Since Marvin Gates’s black metal sculpture is entitled Barbara, we’ll adhere to the convention of adopting feminine pronouns when referring to the likes of large, ocean-going vessels. Thus, “it” becomes “she,” and she is both a work of art and an art gallery: a rectangular mobile home to a constantly changing selection of eight small paintings that has moved across the cultural landscape of New York City for the last five years. She is an inveterate voyager; but notwithstanding her hull of steel, she’s no Queen Mary, being closer in size to a dinghy. Whether or not she’s seaworthy remains to be seen – her boxy, epoxy and rubber-coated steel structure is so seamlessly engineered that she might well float – but you’d never confuse Barbara for a boat.

She has frequently been mistaken for a dumpster, but in the wink of an eye, one person’s dumpster may become another’s bunker. The terse term “art cart” sounds smart, although most of her admirers (and detractors too) know her on a first-name basis. How could that be otherwise, what with the word BARBARA emblazoned in large block letters above the doorway that invites us to enter her realm. The disarming moniker sweetens her dark, decidedly institutional façade. The final say on her nomenclature belongs to Marvin Gates, the jocular artist-provocateur who made her. “I had to name her something,” he confesses; and having done so, he defines his creation as “the museum on wheels,” humorously Frenchified as Le Musée à Roulettes.

Any and all of these names are apt because Barbara is quite the Chameleon. She can blend in alongside trash receptacles on New York’s Lower East Side, yet also find herself at home on Manhattan’s Museum Mile, or in front of the bluest of blue chip Chelsea galleries… whose piqued owners rarely enjoy her presence on their turf. Not to overstay her welcome, and constantly in search of new art-appreciators, Barbara is perpetually on the move. While everything about her is scrupulously legal, her habitual running around town is as anarchic as the law allows. Meandering from one arty venue to the next, and setting up curbside where the labyrinthine laws of New York City permit, Barbara is full of mischief. All four of her wheeled feet are planted firmly on the ground, but an implied question lingers in the air, namely: is the difference between a vending stand and a swank art gallery merely a matter of price?

If she could speak for herself, Barbara might answer by quoting Walt Whitman: “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then, I contradict myself. I am large. I contain multitudes.” Inside her confines, we find not multitudes, but rather a rotating selection of eight carefully constructed paintings, with room enough for a snug quartet of viewers in the bargain. When you pass through her doors, her Spartan exterior gives way to a surprisingly comforting emotional note, one that is both welcoming and welcomed. Inside, benches invite guests to be seated, and the close quarters oblige us to scrutinize Gates’s paintings from a proximate distance, so that his little gems fill our field of vision. Depending on your frame of mind, her interior resembles a prison cell, or a monastic sanctuary. A hush prevails, and how rare is that on the sidewalks of New York? Say a few words, and they sound like they’re muffled in an echo chamber. As your eyes adjust to the ambient dark, the defused natural light that filters through slatted windows makes the paintings glow in their shadowy niches. An unexpectedly hallowed overtone suffuses this place, where the sunlight and the paintings on view all change in the course of time.

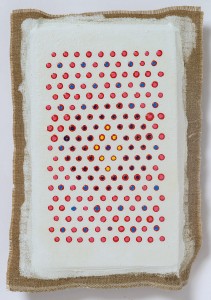

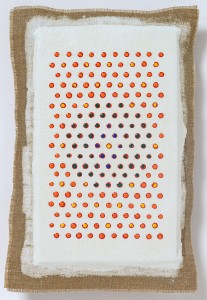

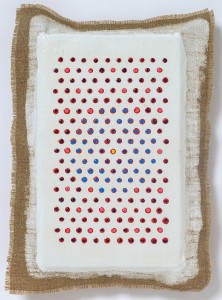

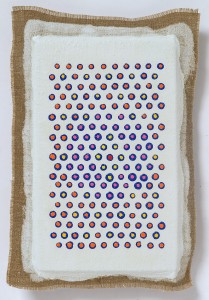

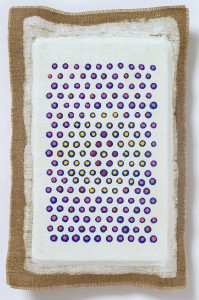

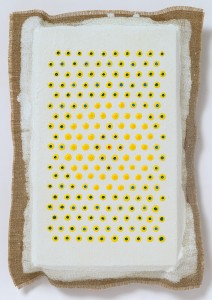

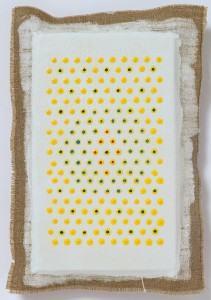

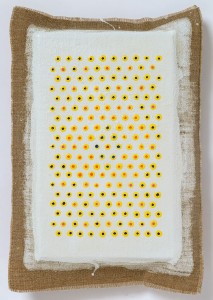

Precisely how large is Barbara? By design, she’s 5’x8’x3’, which qualifies as the exact maximum legal limit for a vending stand, as defined by the codes and rules of the City of New York. Her creator, Marvin Gates, has a hard-won respect for the letter of the law, being the only artist I know who’s earned both a Guggenheim grant and a fifty-three-month stint in the penitentiary for bank robbery. Chalk up this colorful biographical detail to youthful desperation, and understand that in ways great and small, Barbara represents the consequential aftermath of Gates’s prison experience, which transpired thirty years ago. It’s certainly fair to say that four and a half years of incarceration taught the artist a great deal about time, which is well served in his lovingly labor-intensive enterprise. All of his newest works share the title The View from My Prison Window, time-stamped every hour, so that we get the view – a stunningly limited view – from 05:00 through 22:00. In keeping with Paul Klee’s injunction, everything starts with the point – or if you prefer, the dot – which Gates carefully renders using the sharp tip of a slender, sable-hair brush and/or a syringe.

Ten equidistant dots of overlapping primary colors are set down in a row, nineteen rows in all. Human nature being what it is, we strive to connect the dots. Immediately they form a line, but in short order we discern other fleeting figures teasing our retina. Colors begin to vibrate, and initially static forms start to sparkle and spin. Comprised of eighteen close variants, The View from My Prison Window constitutes a rotating show in every sense of the word. This stylistically unified series was painted on linen-covered steel. Since the medium always matters, you might say that Gates’s newest works manifest a steel fist in a linen glove.

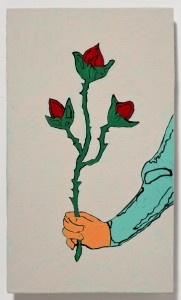

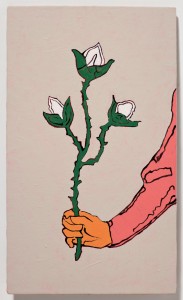

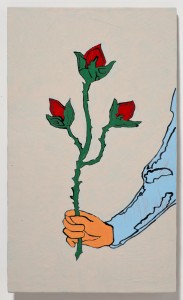

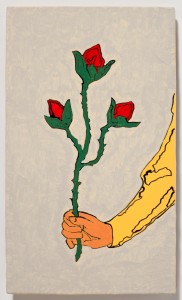

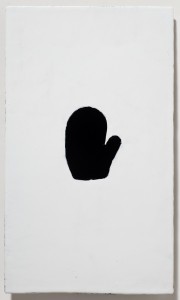

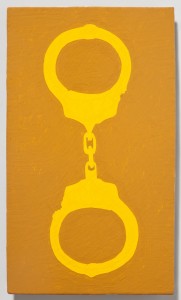

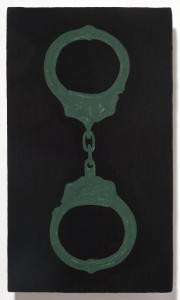

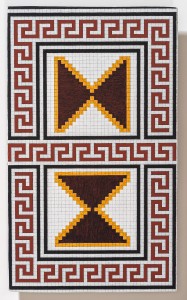

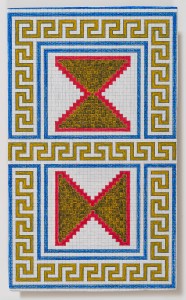

Barbara’s walls feature stylistically varied works, all hung vertically and painted with oil and enamel on sandblasted and powder coated steel. Some are geometric abstractions, such as the impeccably wrought Meander series. Other representational works’ straightforward iconography appears easy to decode. One metal panel represents a chrome yellow handcuff whose figure-eight shape is set against a pumpkin-colored background. Another depicts an extended fist gripping a thorny stem that’s blossomed into a trio of blood-red roses. Gates’s intermingling of diverse styles serves a dual purpose. His rigorous abstractions help us appreciate the formal virtues of his poetic narratives. Conversely, the artist’s representational images encourage viewers to seek symbolic subtexts in his non-objective works. Thus the 18 paintings that share the title Meander, which may be a verb or a noun, suggest both the meandering course of the artist’s remarkable life-journey, and the Greek decoration whose interlocking forms have stood the test of time. Collectively this stylistic potpourri provides a miniaturized anthology of what’s hot and what’s not in the museums and galleries that surround Barbara when she’s out and about. Thus, among many other virtues, she functions as an art critic.

She is also a dedicated traveler, and as such she invites our own flights of fancy. Sea-going? Not yet, but given the likes of Hurricane Sandy, hey, you never know. Gallery-going? Zealously. You may find her uptown, or downtown, or on a street corner near you; and if you do, she’ll linger in your mind’s eye long after she departs.

Gerard Haggerty is an artist and author who writes for ARTnews magazine, and he teaches at Brooklyn College, City University of New York. His work has won multiple grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Ford Foundation.